Krapp's Last Tape With Film Star Gary Oldman: A Review

York Theatre Royal took a managed risk. It paid off, says Liz Ryan.

Be again, be again. All that old misery. Once wasn't enough for you.

Krapp is dying. Once a year, on his birthday, he commits a few words to tape about the state of his life. Now he has boxes of tapes. And every year according to a strict rotation only he understands, he listens to and comments on a recording from earlier years. This year he’s listening to one he made when he was 39 years old.

Krapp’s Last Tape plays tricks with time. Samuel Beckett’s monologue was first performed at London’s Royal Court Theatre in London on October 28, 1958, directed by Donald McWhinnie and starring Northern Irish actor Patrick Magee, whose unique ‘cracked’ voice fascinated the Southern Irish playwright.

Inspiration for the play came also from his recent encounter with the (then) last word in sound technology when, as a rising literary star, he visited the BBC’s Paris studios. So 39-year-old Krapp is using state-of-the-art recording equipment to comment on a still younger version of himself who is in turn reflecting on an earlier time in his life:

“Sneers at what he calls his youth and thanks to God that it’s over. (Pause.) False ring there,” says the man on the tape about his reflecting 20-something-self to the old man who is listening to him. They are all four, from youth to age, the same person — but to what extent? “Memorable equinox,” says a jotted explanatory note accompanying the box of tapes. “Memorable equinox?” repeats the older Krapp, mystified. He thinks his younger selves are idiotic, and by the end of the performance we do too.

A year ago, film star Gary Oldman visited York with his family to show them the theatre where his professional acting career began in 1979 as a pantomime cat. CEO Paul Crewe took the Oldmans on a private tour of the renovated and extended building and whilst he did so a project took shape.

“It’s impossible to think that I have spent nearly the entirety of my professional life… in front of the camera,” muses Oldman in the programme. “But, camera or not, the theatre never leaves you.”

It was a risk. Oldman’s many film-acting accolades include an Oscar for his portrayal of Winston Churchill but his theatrical experience is by comparison meagre. And yet here he was, someone the team at York Theatre Royal scarcely knew except from the silver screen, being handed almost total creative control over the performance. Would egomania get the better of him? It was a possibility, and this perhaps explains why the press performances happened midway through the run. Better to get any vanity-project embarrassments sorted out before the vultures of Fleet Street and the New York Times got hold of them.

I’m happy to report that Oldman was entirely restrained in his directorial decisions. As befits a play by a future Nobel Laureate, whose words extend over a mere nine pages, he used extended periods of silence whilst he fumbled around with bananas and tape canisters as his weapon of choice. He span those pages out to 50 minutes and yet there were no longeurs: the business of finding the correct numbered spool was both realistic and quite funny. Lighting (by the award-winning Malcolm Rippeth) came from two pendant lampshades casting pools of orange against the encroaching darkness, whilst voice-recording sound engineer Gary Canale at Studio One teased convicing life out of an ancient piece of kit. Oldman’s voice on tape, sounding younger, was a complete performance in itself.

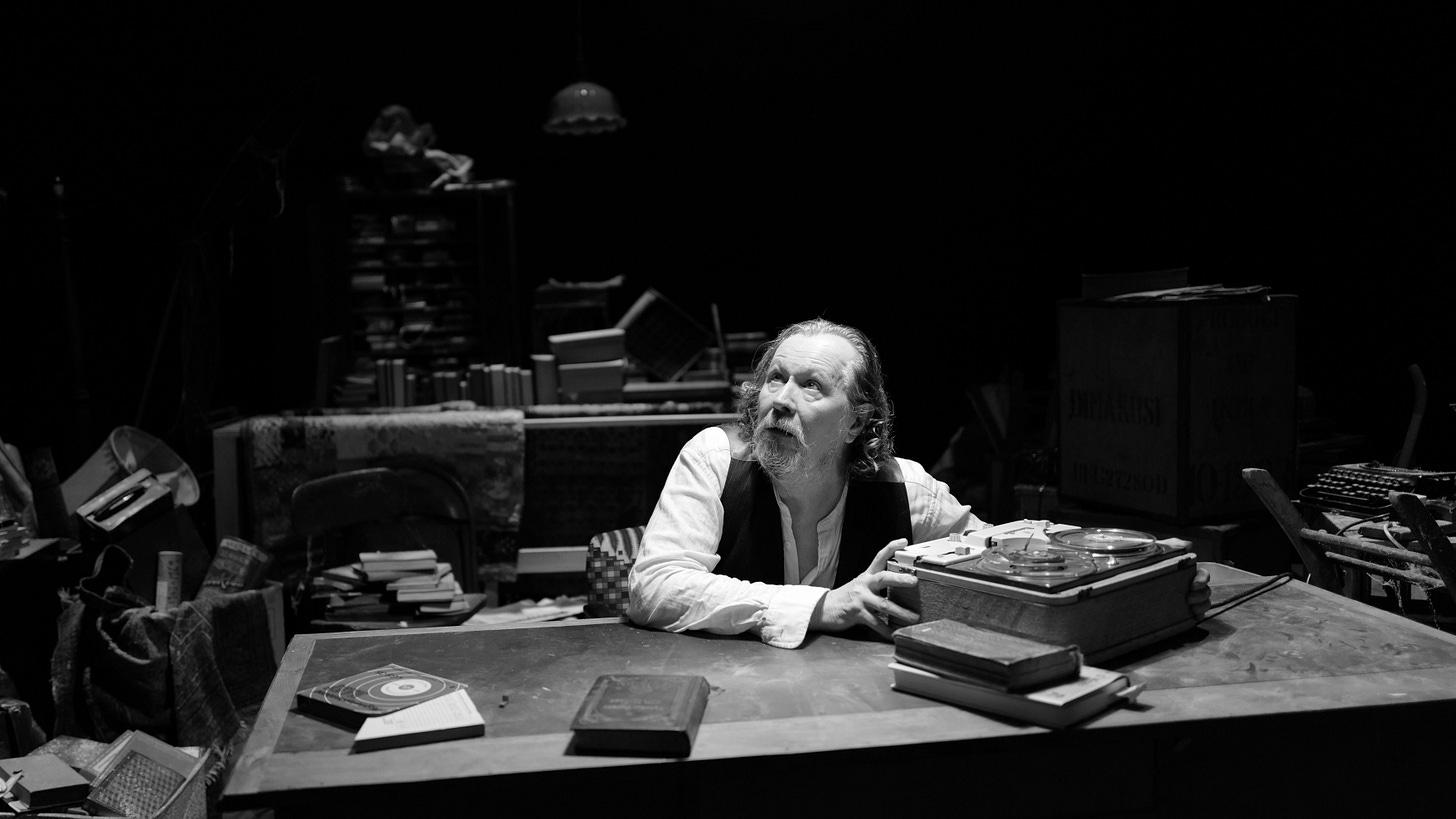

His only extravagance was the set. The dismal themes of the play lend themselves to a sparse backdrop. But Oldman granted himself a filthy Aladdin’s cave of accumulated clutter; the type of dirty hoarding that might lead an old man’s neighbours to make anxious phone calls to social services.

When Samuel Beckett wrote this play he was already a cult figure in theatrical circles and becoming famous. Born in Dublin in 1906, he grew up in the affluent suburb of Foxrock as part of the ruling Protestant Ascendancy. Ireland, at that time, was still governed from Westminster as part of the British parliamentary state. It was not a colony but returned MPs to the legislature. The political turbulence and considerable actual violence of the Easter Rising (1916), the War of Independence (1919-21), and the Civil War (1922-23) didn’t affect him directly but formed an unstable backdrop to his childhood and adolescence. When he was born, the prosperous section of the Irish population (largely Protestant) enjoyed the privileges of an Empire that encompassed the globe. When he finally left Ireland for good, in the late 1930s, he was the ungrateful citizen of an impoverished little theocratic state ruled by Catholic priests whose religion he didn’t share.

His life story has unexpected parallels with that of his fellow-Parisian, the fashion designer Yves St Laurent, also plagued by depression and substance misuse throughout his career. The St Laurent family’s comfortable life in Oran was ended by the Algerian War. A grief you can’t name because it’s so politically beyond the pale in the circles you move in must be a hard thing to bear in silence.

Krapp is the most autobiographical of his writings. Beckett himself excelled at school, attended Ireland’s best university (Trinity College, Dublin) and, after an undistinguished interlude as a teacher, took up a less-than-arduous post as lecteur d'anglais at the prestigious École Normale Supérieure in Paris on the recommendation of a tutor.

Knocking around in the French capital, he encountered James Joyce. The two expatriot Dubliners hit it off and Beckett became Joyce’s protegee and acolyte — his presumed literary heir. But it was a hard burden, and over the next few years of Continental comings and goings, Beckett experienced a failed love affair with one of his cousins. The relationship fell foul of family disapproval and she later died of TB. He adopted a dissolate lifestyle which ended abruptly when he was stabbed by a French pimp.

The best thing about the stabbing was that a keen amateur musician called Suzanne Dechevaux-Dumesnil, whom he’d met at a tennis club, began to visit him in hospital. They moved in together, joined the French Resistance at the outbreak of War, and when the Nazis came for them went on the run together through rural France. (His famous phrase "I can't go on, I'll go on" from his novel The Unnameable is believed to have had its genesis in that extended, half-starved, route march through enemy territory.) They eventually found sanctuary on a remote farm in Roussillon near the Spanish border.

At the end of the War, when he was almost 40, Beckett had a few scraps of published writing to his name, a Croix de Guerre medal awarded by the French government for his Resistance activities, a nasty healed wound in his chest and notably bad teeth. His great literary future, as heir to Joyce, was behind him and he fell into aimless drinking again. His late father had been rich enough to leave him a tiny allowance, and he lived on this, supplemented in Paris by whatever Suzanne could bring in from sewing.

Then, on a reluctant visit home to Dublin to see his sick mother, who was by now dying of Parkinson’s Disease, he seems to have stood on a pier or rocky outcrop and had some sort of epiphany. Instead of apeing Joyce’s erudition, and his over-the-top Finnegan’s Wake style, he should be finding his own way. And that meant mining his own consciousness and the nihilistic darkness he always carried with him.

Returning to Paris he threw himself into writing three short novels (one is more like a philosophical treatise) and a humourous play called Waiting For Godot which he wrote almost as an afterthought. The rest, as they say, is history. But it wouldn’t have been history if loyal Suzanne hadn’t taken it upon herself to troop round all the publishers in Paris in an effort to find someone who would take the manuscripts.

There are plenty of lines in Krapp that can be mapped onto episodes in Beckett’s own life if you are so inclined; the death of his mother, his midlife despair and febrile resurrection, a memory of floating downstream on a punt with the lost love of his life. But it’s impossible to escape the conclusion that Krapp is Beckett himself, or what Beckett would have turned into, if he’d never met Suzanne. Psychologists say that children can overcome any amount of neglect and abuse if they are taken in hand by a good adult who believes in them. Suzanne may not have been the love of his life, but this was her role: she continued to believe in him long after he’d lost faith in himself.

Dust. Fragments. Patrick Magee’s performance is said to be the definitive Krapp (you can view the 1972 television version here). But it would be invidious to compare his intimate small-screen performance with the theatrical need to reach the back row of a 760-seater auditorium. Oldman’s Krapp has more physical presence, more chi, but this is juxtaposed pitifully with his stiff joints and failing mind.

Yet the old man has a terrible clarity on some subjects. He snorts with derision at optimism, the aspiration, the verbal and literary pretensions, of his younger selves. Yet he still goes to the dictionary to find the meanings of obscure words he has forgotten but which he previously used with precision.

One word he does remember is “chrysolite”. His lost beloved has eyes like chrysolite. Turning to Google I find with a shock that this is a semi-precious olive-green gemstone often shot through with yellow and other colours. It is an accurate description of the hazel-green eyes often found in populations with Scottish and Irish ancestry. You could describe my own eyes as chrysolite, and those of my father and brother which are identical. A lesser pen would call them ‘green’ or, if you wanted to push the boat out, ‘emerald’ but that would not be accurate.

So here is a still-youngish man, the author of a magnum opus which sold 17 copies (“eleven at trade price to free circulating libraries beyond the seas”) who really does care, passionately, about the correct deployment of words. Yet everything he writes and utters betrays his stilted — indeed, constipated — inability to transcend the artistic formulas and pretentions of his time; he watches himself watching himself writing. The discreet but multiple bowel-disorder references, the endless toilet-sitting it must have entailed, suddenly made sense.

Krapp struggled to become an artist but never quite made it. Oh, not through the failure of his book to sell but because he couldn’t crack out of his solipsistic shell to embrace women and love. Instead, despite his carefully constructed descriptions, the younger Krapp comes across as using language to separate himself from his own emotions rather than to reveal them — and even to lie.

“False ring there.”

I was nervous about seeing this play. I knew its reputation for bleakness, and my own father’s cynical and disappointed last few years, during which he remained lucid but was in many ways insane, were so difficult for us all — and so painful for him — that I wasn’t sure I wanted to enter that territory again. Yet there is a perverse comfort to be had when a great writer turns his or her attention to the unbearableness of life.

“Be again? Be again?” roared Oldman. “Once wasn’t enough for you?” It was a reminder that youth, with its many psychological torments, is nonetheless when we are most alive. His rough snort of derision at the inauthenticity of his midlife self rings true also to those of us who feel squirming, shuddering embarrassment when we contemplate what we used to be. And that’s most of us, if we’ve undergone any growth, change or self-reflection at all.

Krapp’s ‘message’ is a tragic one for Krapp, but a comforting one for everybody else. That love matters, and in it you will find your art.

I was wrong about the audience too. I thought ageing punks (Sid And Nancy) and Harry Potter fans (Sirius Black) would be there in numbers. But this didn’t feel like a hero-worshipping gathering whose members were unfamiliar with theatre etiquette. The theatre’s memo about refraining from applause at the start of the show had clearly landed with the audience. The film star’s entrance was greeted with silent expectation rather than cheers. Not a single phone buzzed throughout the performance, which was a miracle when so much depended upon silence.

There was, when I attended, a higher-than-usual number of clean but scruffy middle-aged men in the best dress-circle seats. But that very casualness spoke of an easygoing familiarity with theatre attendance. No screaming film fans — instead the audience’s attitude was quietly reverential, as though they were watching the Pope do Mass. To emphasise that we were watching An Historic Theatrical Event, the antique tape recorder onstage was the very same prop used by actors John Hurt and Michael Gambon when they too Krapped.

Then it dawned on me: this was not just a theatrical occasion but an industry gathering. Oldman expressed his hope in the programme that his film-star status might draw first-time theatre-goers in. Perhaps it did. But it felt as if every professionally trained actor, theatre director, film producer etc within practical travelling distance had also turned out to see it in the hope of getting a master class.

This knowledgeable audience didn’t quite rise to a full standing ovation. But Oldman gave a solid performance that deserved and got a solid reception. Even if it was impossible for him to replicate the luminous pain in the eyes of the extraordinary Patrick Magee, he did more than enough to show that he can act on stage — and he mercifully refrained from Acting with a capital A.

The lovely York Theatre Royal is a lucky theatre. She’s come through the ages since the 18th century with the ghostly Grey Lady watching over and protecting her. I’d put money on this lucrative show going to Broadway.

Krapp’s Last Tape at York Theatre Royal runs to May 17. Returns only.