Snag List

Bradford's new Arts Centre opens this week. It has a multi-cultural agenda. Is it going to work?

The paint is still wet on the doors as I push my way into Bradford’s brand-new arts centre. Bradford is — depending on how you measure it — the 8th largest city in the UK. Situated in the Pennine foothills it is also the highest, averaging 325m elevation against London’s 20m. That will be useful if sea levels rise. And it’s the youngest in Europe. According to the 2021 Census 29% of the population is under 20 years old.

It is also troubled. Take any unwelcome social metric you like — child poverty, crime, ill-health, life-expectancy — and it shows up in a bad place. Disability claims for children are 23% higher than the national averge and it has the 10th highest infant mortality rate.

Grim. But try raising this with any of Bradford Arts Centre’s team and you’ll be told sharply that “Bradford has had a bad press”. Which, over the years, it has. Bradford’s ethnic profile — 32% Asian or Asian British with the largest single subgroup (25%) Pakistani — regularly incurs the ire of right-leaning commentators. All the same, no smoke without fire.

But today is a happy day. The press is being welcomed in to showcase the new facilities, the culmination of 30 years’ creative endeavour in which an Indian dance company, Kala Sangam, first rented rooms in the rundown former General Post Office, then bought the building with a sitting tenant (Bradford Council), and at last has full occupancy and the resources to make something of it. The millions required to refurbish the Grade II Listed building have come from the Department of Culture, Media and Sport and the Heritage Lottery fund.

Heritage funds often dwarf those available to the arts and they love a new use for a beautiful old building, especially if it comes with a viable business plan. Designed by architect Henry Tanner and built in 1886 in the Northern Renaissance architectural style (with French overtones, why not?) St Peter’s House measures 224ft across and has a spectacular polished granite frontage. Years of post-war neglect left it a rabbit warren of tiny, divided rooms, with a narrow staircase, a creaking and unreliable “Thoroughly Modern Millie” lift, and no obvious door in. Stripping back the plasterboard revealed a host of original features that had been covered up for decades.

Now it has:

A new Theatre with 170-seat capacity, two wheelchair spaces, sprung dance floor, state-of-the-art sound and lighting

New dressing rooms and a shower backstage (fully accessible)

Five studio spaces, including one dedicated to community and education work. Two studios have sprung floors, one is a dark space that can be used for working with projection and other tech

Three conferencing and event spaces: The Hall, The Weston Room and the Clocktower Suite, with two additional meeting rooms

A new lift, giving step-free access to all floors of the building for the first time

A new, central main entrance

Step-free entrances on either side of the building

BCB Radio will have three state-of-the-art recording studios

Free co-working flexi space ‘Sangam Lounge’

Cafe (opening later in 2025)

Changing Places toilet changing-places.org

Given Bradford’s above-average disability levels, the Changing Places toilet is particularly important. It’s a large, private space with a hoist and other facilities so that even if you are multiply disabled and require incontinence pads and catheters, you can still attend to a call of nature with dignity.

I know what you’re thinking. “The squeakiest wheel gets the most oil.” And Bradford is certainly a squeaky wheel. But it’s not that simple. There was a latent need for conference facilities in the city so from the very first day, with hard-hats still in the building, they were booked out.

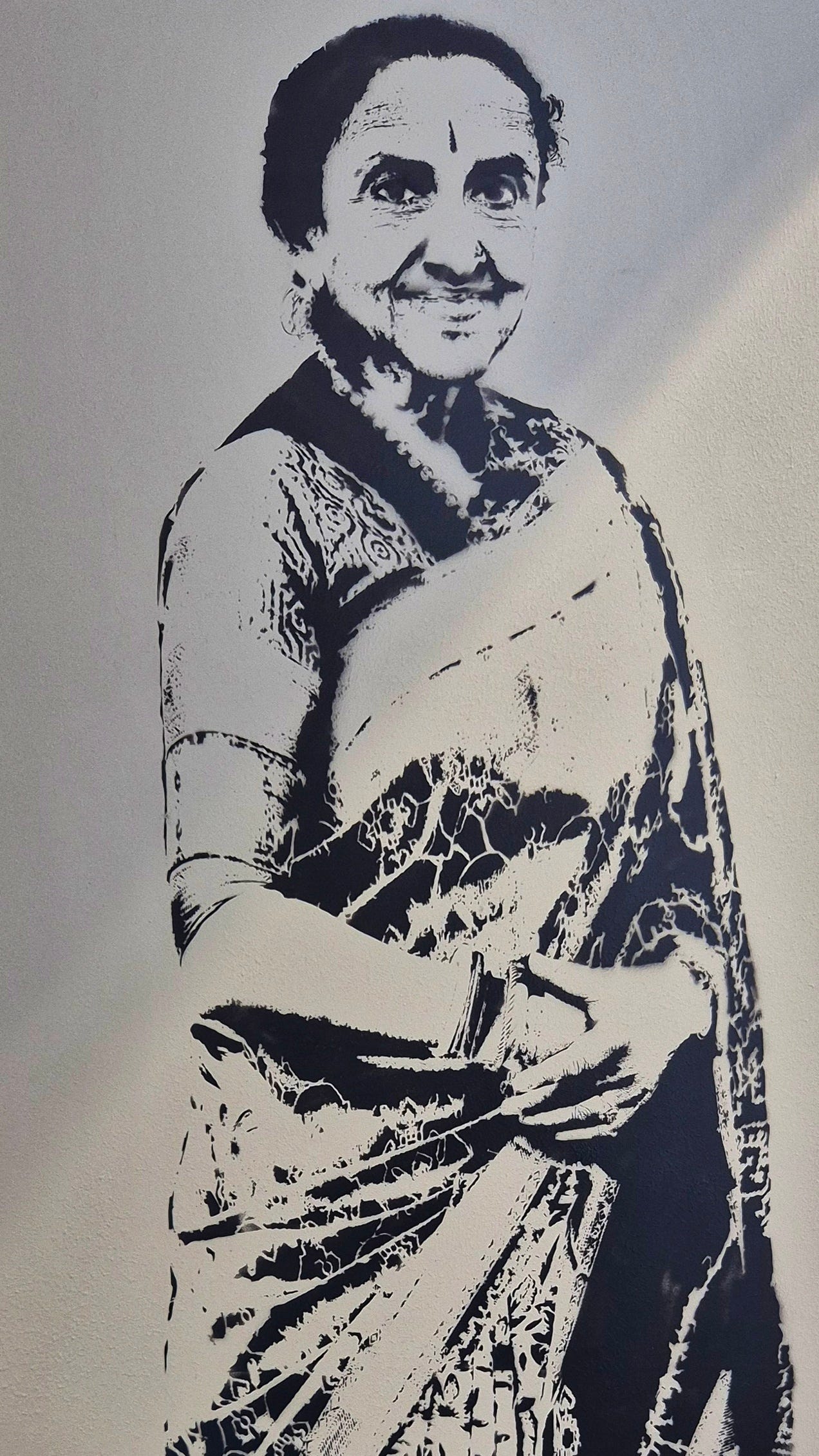

“We’re standing on the shoulders of giants,” says CEO Alex Croft. The giants he is referring to are Dr Geetha and Dr Shripati Upadhyaya, founders of Kala Sangam; and also the company’s tradition of strong governance which resulted in a Board with the professional capacity to steer an ambitious project.

The other advantage enjoyed by St Peter’s House is its location by the Cathedral on the edge of Little Germany. This is a small district of astonishing architectural quality consisting mostly of export warehouses built in stone to last forever at the height of Bradford’s 19th-century prosperity. Bradford Playhouse is nearby, composer Frederick Delius reluctantly learned his family’s merchant business here, and there’s nothing city planners love more than a cultural quarter.

Those who built Bradford’s world-leading industrial might in Victorian times were mainly Eastern European, often Jewish. Ethno-nationalists might complain with some justification that “immigrants built Britain” is a myth and a trope. But some UK places really were built on successive waves of immigration, and Bradford is one of them.

To be in the room with the new Arts Centre team, many of them Bradford born-and-bred, was to be profoundly aware of Bradford’s unique inheritance. Bradford is not as other cities. Things that work in Bradford might not work elsewhere. And yet, Bradford’s challenges are so acute, that if things can be made to work here, who knows what else might be possible.

When local opinion was scouted to find a name for the new facility, the overwhelming majority opted for ‘Bradford Arts Centre’. It does what it says on the tin (very Yorkshire) but, more importantly, it signals that it will not be owned by any single section of the community. It’s for everybody. I felt everyone on the team was utterly sincere in saying that. Ethnic exclusion will be addressed via eclectic programming, financial exclusion via almost laughably low charges for tickets and studio hire. Full disabled access goes without saying.

And yet… the professional arts world has been so progressive, for so long, that its inhabitants seem disconnected from how disconnected they are. Can you really talk about welcoming everybody in one breath and in the next talk about expanding the offer to the LGBTIQ+whatever? Don’t they understand how insufferable the blue-haired weirdo brigade are to just about everyone who doesn’t live inside the bubble?

Alex Croft is determined to do something for the “protected characteristics”. The 2010 Equality Act has, indeed offered valuable protections for individuals who find themselves discriminated against on the grounds of age, disability, gender reassignment, marriage and civil partnership, pregnancy and maternity, race, religion or belief, sex, and sexual orientation. But out in the field, the Arts Council-encouraged tendancy to think of those characteristics as groups, or worse still, intersectional funding boxes, has not been wholly benign. You cannot discriminate against individuals on the basis of sexual orientation, or because they have taken meaningful steps towards gender reassignment; but this does not mean you are legally required to indulge every kind of alphabet nonsense in the way many in the arts community assume that it does.

Don’t get me wrong, the arts have always offered shelter to misfits, and people can make work about whatever they want. Jaivant Patel Company’s upcoming dance piece Astiva (Oct 9 & 10), which we were privileged to glimpse in open rehearsal, is a perfectly valid exploration of the lives and loves of British-Indian gay men. But far from expanding the offer to the strange and nebulous community known as “queer” isn’t it already vastly over-represented in arts programming compared with the rest of the population?

I took a breath and asked about “the disconnect” during the Q&A. I received some detailed and thoughtful answers, particularly from Gianluca Vincentini of Mobius Dance. No, we don’t seek to proselytise. We lay the work out there — it’s up to the audience to take what they want from it. We’ve toured our work to unexpected places and it’s gone down well. Mobius Dance present The Long Summer Day on Oct 17 — it’s “a celebration of queer body and soul, in harmony with the transformative light of the sun”. I’m sure it’s beautiful — but what does ‘queer’ even mean any more? Isn’t it time we gave this fashionable but alienating adjective a rest?

Over lunch I found myself acting as Patient Zero for their food offer to coeliacs, not the first time this has happened to me when visiting newly opened facilities. I sat next to a third-generation Pakistani Bradfordian who was involved at a senior level with the renovation. “My grandfather when he arrived had no education,” he explained, considering how good the city had been to his family and the consequent affection they felt for it. He was living back in Pakistan when he heard a job was available — in Bradford the connections between home and South Asia are fluid, which is why after multiple generations assimilation is not inevitable.

Hilariously, it transpired that Bradford’s legendary Dr Saeed (Unmasking Dr Saeed: A New Play Explores A 30-Year Medical Fraud) had been his family doctor and a family friend, dropping by frequently for supper. They all liked him very much; thought him a good doctor. Theatre in the Mill, where A Teaspoon of Shampoo was staged in March this year is a few hundred yards away from the Arts Centre, on the University campus. And yet, despite his personal connection with Dr Saeed, he’d not heard of it.

Okay. Difficult question time. The Markazi Masjid, European headquarters for the Tablighi Jamaat, an offshoot of the Deobandi movement, is located just 10 miles away in Dewsbury. The conservative Islamic Deobandi tradition is well-represented in Northern England and notably disapproves of music, singing and dancing. Had he encountered, in his role, any difficulties or conflicts with fundamentalist Muslims in the area?

He seemed both startled and slightly offended by the enquiry, but I offer no apologies. If Roman Catholicism can be put through the wringer, then so can every other religion. The answer, when it came, was a passionate and slightly garbled defence of freedom of conscience within Islam. People do not always agree but they let each other alone to get on with it.

Do they really? I think about the smallish, downcast, shifty-looking South Asian youths on the railway platform at Bradford Interchange. They look as if they have self-esteem issues. They are far from resembling the stereotype of confident, young, engineering students from good families who make up a disproportionate number of jihadists and suicide bombers. (Gambetta & Hertog, Engineers of Jihad, 2018)

I think about the time I was barked at, most unpleasantly, on the edge of the Sahara desert, by a member of the hotel’s staff who took exception to my painted toenails in strappy sandals as I made my way to the dining room. And then I see an older Bradford lady in full niqab with her face covered, hopping cheerfully into the train by herself with her own bare tootsies fully on display to her ankles. She too was wearing sexy sandals.

Does that niqab get whipped off and put away in her bag before she reaches her destination? It’s possible. In Bradford, at least, it seems like the box of Islamic belief is being thrown up into the air and the pieces are coming down in various configurations. Many people are trying to muddle their own way through. But, just as that Muslim arts worker had not heard of A Teaspoon of Shampoo even though it was being performed to considerable BBC fanfare just 250m away, maybe there is less Muslim ‘community’ than non-Muslims imagine and maybe individuals are still not having the wider conversations they need.

“It’s time we abandoned the victim narrative,” said one British South Asian artist during the Q&A session. My impression is that the sheer size of the Unite The Kingdom march in London last month, combined with the success of Reform in the polls, has rattled progressive arts people to the point where some conversations are now possible that weren’t before. But it’s difficult to make a start — to say something that will break the groupthink. You know you’re going to be treated like a bad smell in the room. They might all turn on you and bite you, so that wounded and outcast you’ll die like a lone chimp in the forest.

“In the past, the white working class got nothing,” admits Amer Sarai, Head of Community Engagement. That, she believes, is something this year’s Bradford City of Culture festival has taken pains to avoid. And the Arts Centre has committed itself to being a keeper of memories — an essential role in a city where successive waves of immigrants may not be aware of what has gone before.

Would you host a St George’s Day celebration? I ask her later. One of Bradford’s finest buildings is the St George’s Hall so it’s not an entirely random or mischievous question. “Yes, yes. Of course,” she asserts.

Yet it struck me that there was a distinct absence of obviously working-class white men in that Q&A. They were all upstairs putting the finishing touches to the wiring.

It’s easy to poke fun at the inclusivity agenda. But the staff instantly ‘got it’ when I explained my gluten difficulties at lunch-time. I remember all those staff meetings and workshops over the years where I’ve been expected to dine off the sandwich platter garnishes and a few crisps whilst every else tucked into sausage rolls. Sometimes it was ignorance; once it was bullying. The routine disability awareness on display at Bradford Arts Centre also puts my elderly mother’s GP surgery (an actual NHS medical facility) to shame.

But there’s a snag list. And a big snag on the list is that, under a London-dominated Labour government struggling to balance the books, the funding to establish the City of Culture’s permanent legacy is in doubt. The funding for both the Arts Centre and the Festival happened under a Tory administration.

I don’t envy the role of Programme Manager at Bradford Arts Centre, balancing conflicting values and attitudes to create a cultural offer that genuinely welcomes everybody. But in that room I saw a determination to make multiculturalism work in Bradford. If only, in the light of Britain’s political situation, because the consequences of it not working are uncomfortable to contemplate.

Bradford South Asian Festival: Shadmanny!

Two days of family friendly music, film, dance, food and storytelling on the theme of weddings. It all kicks off with a ‘baraat’ parade — an authentic wedding procession with a Yorkshire twist. Bradford Arts Centre, Oct 11 & 12, prices vary but many are ‘pay what you can’.

It takes about three days’ work to put together an Yorkshire Theatre Newsletter edition. If you found this piece interesting, useful, enlightening or helpful please consider buying me a coffee or, better still, becoming a paid subscriber.

UNDER CONSTRUCTION: How To Create A Playwright (coming shortly)

Best wishes

Liz x