Yorkshire Theatre Newsletter started life as a highlights magazine in December 2020. Lest we forget, there was something to write about — distanced performances, online performances, general, lockdown craziness. But to do highlights well takes a lot of research. Eventually, I found a full-time admin job in the healthcare sector. It was a meaningful step at the fag end of the pandemic — especially as I’d spent most of the previous two years poleaxed by isolation, job loss and bereavement — but it proved infinitely more stressful than I expected. So the regular listings component of my newsletter had to take a backseat for a year or two in favour of occasional in-depth theatre reviews.

Now I can see the way clear for the next few months to devote more time to my Substack. Restoring highlights content will take a few weeks to ramp up (research is culmulative) but I have made a start and you will find one or two of next week’s highlights in Section Two.

But first, I hope you enjoy this arts-orientated travel piece. Did I find what I went for? I think so.

You’d be forgiven for thinking the building pictured above is the legislature of a medium-sized country. You’d be wrong. It’s Teatro Massimo, the third-largest opera house in Europe.

When a friend gave me lastminute.com vouchers for Christmas I discovered an unaccountable yearning to visit Palermo. For the culture, the street food, a few days of warmth and sunshine to lighten the January gloom. So I rationalised it to myself, and it was true.

But it wasn’t the real reason. I actually wanted to find out more about the Mafia. But, as usual, my subconscious was miles ahead of the rest of me. So this secret motivation only clicked into focus a few days before my budget Ryanair flight (sadly, no relation) took off for Aeroporto di Palermo Falcone e Borsellino in Sicily.

Teatro Massimo on the Piazza Verdi in central Palermo isn’t a bad starting point. These steps outside the opera house formed the backdrop to the famous, if somewhat histrionic, Godfather III scene where anti-hero Michael Corleone finally meets his karma. Its opulence reminds us that since the time of the Ancient Greeks the natural condition of Sicily, blessed with rich volcanic soils and a perfect position at the crossroads of the Mediterreanean, is to be very wealthy indeed. Even if that wealth has never trickled down to everybody.

A Nun’s Vengeance

The theatre’s story begins in 1864, shortly after the unification of Italy, when Palermo Council launched an international competition to find an architect. The competition was won — unsurprisingly, this is Sicily — by local boy Giovan Battista Filippo Basile and when he died the work was continued by his son Ernesto. Opening night didn’t happen until 1897; Giuseppe Verdi’s Falstaff conducted by Leopoldo Mugnone was the first show.

Everything about Teatro Massimo is on a grand scale. When I visited they were building the set for Otello (Jan 24-30, E24.20-E132) on a stage so huge that, according to our guide, for one Belle Epoch performance it effortlessly hosted two white horses and an elephant at the same time.

This flamboyance extends to the building’s supernatural life. The theatre was built on ecclesiastical remains and is said to be haunted by a nun. York’s Theatre Royal sits on the site of a medieval hospital and is nun-haunted too. But the Yorkshire Grey Lady merely manifests from time to time, walking through walls and scaring the life out of Artistic Associates. Massimo’s aggressive nun-ghost prefers an interactive approach, shoving anyone she dislikes down the main stairs.

My initial attempt at finding the Mafia misfired. To occupy my first evening in Palermo I’d booked the Anti-Mafia Heroes Walking Tour. The rendezvous was a modest cafe-restaurant near a plaque marking the birthplace of famous anti-mafia lawyer Giovanni Falcone (who is also commemorated in the name of Sicily’s main airport). I wandered confusedly through the rundown alleyways of Palermo’s boho Kalsa district with my data-gobbling Google Map until it dawned on me when I re-checked my email that the tour had been cancelled two hours before.

Mafia — and No Mafia!

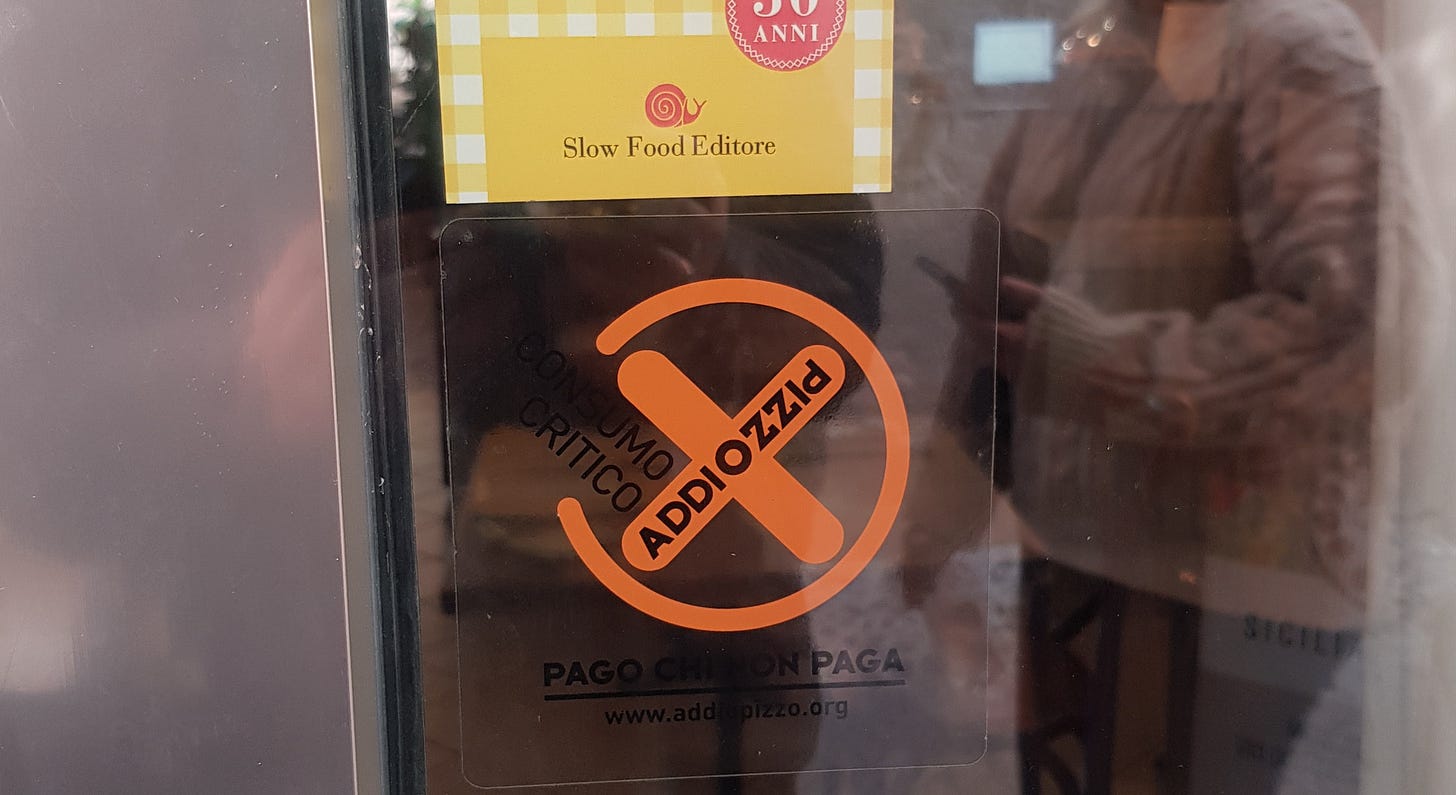

My second attempt was more successful. Addiopizzo Travel is an ethical travel agency only employing hotels, B&Bs, restaurants, farms and transport companies which have set themselves against paying protection money. They also provide tours. The English-language Palermo No Mafia Tour can be booked in advance and leaves from Piazza Verdi in front of Teatro Massimo three times a week.

Our small, randomly brought-together group was led by Attilio, a Palermo native who grew up in the city during the Second Mafia War, 1981-1984. During this period the homicidal Corleonesi Mafia clan (“the peasants”) came down from the mountains and eliminated the more sedate bosses in Palermo, as well as a fair slice of law enforcement and the judiciary. Attilio shared with us that more than 500 people were killed — other estimates are twice as high. As a child he got used to dodging bullets and bodies and thought it normal. From outdoor cafes to la passeggiata, streetlife became impossible and people hurried home before dark. This savage gang exerted an iron grip on the island until well into the 1990s, discouraging inward investment and nixing the economic benefits a tourist trade might bring.

No-one knows how the Mafia began. Much-invaded Sicily was feudal until the British briefly occupied the island during the Napoleonic Wars (1806-15). The British, working with Sicilian nobles, implemented a modern constitution based on the Westminster system. Mountain ‘bandits’ were sometimes spoken of — but no-one bothered to investigate how they organised themselves, if at all. Does the archaic code of conduct which the men of honour pretend regulates their behaviour derive from the Norman occupation or even earlier? No-one knows.

Organised crime on the island comes into clearer focus during the 1860s, at the same time as the newly minted Italian state began to exert its influence. Again, no-one’s sure where the term “Mafia” originated from — Sicilian is almost a separate language from Italian as it contains many Arabic words. But, oddly enough, a raft of Mafia-related terminology was popularised by a play, The Mafiosi of the Vicaria, by Giuseppe Rizzotto and Gaspare Mosca in 1863. The word starts appearing in police reports at around this time.

We walked away from the main tourist area until we came to a small, tree-shaded square somewhere to the north-east of Teatro Massimo. There, Attilio explained to us how the protection racket worked:

You open a small bakery. After a few weeks a pleasant man drops by to explain that he is your “friend” and that it is time you “put yourself in order”. Every Sicilian understands what it means — and if you ignore this invitation you will be subject to cordially escalating threats which finally include hints about where your children go to school. A can of petrol (gasoline) and a lighter might be left outside your door.

Obviously, until the recent past most business owners opted to put themselves in order. Some simpler folk, Attilio explained, even thought the pizzo was a legitimate tax. And once you are under your friend’s protection, certain benefits might come your way. Your local Mafia boss doesn’t want to kill your business. He has an actuary’s shrewd eye for what it is worth and what it might bring in. The pizzo (protection money) is always the most you can bear before you snap, but rarely exceeds it.

And if, say, your new scooter goes missing, instead of reporting it to the police you go to your friend and he will get it returned — for a price. (Because both he and the thief have naturally incurred expenses. It is only reasonable, and much, much cheaper than buying a new scooter and having it stolen again.)

“Un intero popolo che paga il pizzo è un popolo senza”

Something changed in 2004. On the nights of Jun 28 and 29, a group of young Millennials who’d grown up under the boot of the Corleonesi Mafia clan and were sick of it, staged “a provocation”. They covered the whole of Palermo with stickers reading: “A people which pays extortion money is a people without dignity.” At that time, said Attilio, about 90% of Sicilian businesses paid the pizzo — but nobody talked about it. Omerta, the Mafia code of silence, held sway. The stickers set the whole town buzzing.

After months of anonymous stickering, Addiopizzo was born, of which Addiopizzo Travel is an offshoot. Businesses who decline to pay pizzo display a sign on their door, and the effectiveness of this was affirmed when two convicted mafioso were secretly tape-recorded in jail grumbling about how impossible it was to get money out of Addiopizzo businesses.

Naturally, Addiopizzo took quotes from the tapes and stickered the whole of Palermo.

Obviously, 1,000 business owners aren’t a whole hill of beans for an organisation which, at its strongest, infiltrated not merely the highest reaches of the Italian government but also the EU. The rest of the tour focussed on the heroes, martyrs and victims of what almost amounted in the 1990s to a Sicilian civil war as the respectable elements of the Italian state fought to get a grip.

In recent years anti-mafia murals and street art installations have proliferated in Palermo. Attilio took us to see a long, painted wall decorated with the visages of police officers and judges who were murdered in the struggle. To my surprise, it was book-ended by images of two writers — both of whom were lucky to die natural deaths. The first is Andrea Camilleri (1925-2019) who wrote the popular Inspector Montalbano crime novels. The second, less well known outside Italy, is Leonardo Sciascia (1921-1989). Both braved the wrath of the Mob, the Catholic Church and corrupt politicians by telling it how it was. Sciascia, in particular, wrote a great deal about the anomie of Sicilian life. Anomie is what happens when the moral structures of society break down —individuals, and sometimes whole communities, are left floundering either in normlessness or with norms of behaviour radically out of whack.

The stories of those brave anti-mafia crimefighters are as heartbreaking in their way as those involving the firefighters who fought to contain the old Soviet Union’s Chernobyl disaster. Prosecutors and senior policemen knew they would die. General Carlo Alberto Dalla Chiesa, cynically posted to Sicily with insufficient resources in 1982, refused a phalanx of bodyguards because he didn’t want to take them with him when he was assassinated. He died with his wife at his side and a single escorting police officer.

Father ‘Pino’ Puglisi, a priest working in his native Brancaccio, a hard-scrabble Palermo neighbourhood, did only good in the world. He was taken out by the Mafia for… doing only good in the world. He had a football pitch laid out, a fine swimming pool built, took the ghetto children on daytrips to see a bit more of the island and generally worked hard to enlarge their ambitions and opportunities. This, said Attilio, robbed the local bosses of their footsoldiers (his open defiance might also have been a factor) and in 1993 he was shot dead on his own doorstep. According to his killer, his final words were: “I’ve been expecting you.”

Father Pino has since been beatified — a huge step for the Roman Catholic Church which previously denied the Mafia’s existence.

A Step Too Far

Ultimately, it was two prosecutors who broke the Sicilian mafia. Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino facilitated the Maxiprocesso — the largest trial in world history which put 475 mafioso including 19 bosses behind bars. Attilio explained that arrest and conviction wasn’t an unknown experience for the top dons and they were confident that as usual they would be released on appeal. But this time, Falcone and Borsellino’s detailed work led to the identification of a corrupt Italian Supreme Court judge — who mysteriously found himself working elsewhere during the period when the appeals were heard.

In 1992 both Falcone and Borsellino were murdered in bomb ambushes. In the case of Falcone, so much explosive was used that the leading car in his airport cavalcade, containing police officers, flew high into the air and wasn’t found for several days. It was an event that fully justified the Government’s previous decision to build a special court house adjacent to Palermo prison with a roof strengthened to withstand military-grade rocket attacks.

From 1992 onwards the ordinary people of Sicily were signalling that they’d had enough. The Mafia war, the constant killings, the recklessness of the explosions and finally the murder of a priest. A modest public demonstration unexpectedly attracted tens of thousands of furious participants.

The Sicilian Mafia took the hint and has adopted a low profile ever since. The last businessman to be murdered for not paying pizzo was clothing manufacturer Libero Grassi in 1991. It would be nice to think he was acclaimed for his bravery when he took his public stand but, according to Attilio, most Sicilians at that time just considered him insane.

Peace breaks out — sort of

There isn’t a happy ending. With the Sicilian Mafia partially broken, the Ndrangheta from Calabria have risen to international prominence smuggling cocaine from Latin America into Europe. (Italian law-enforcers insist the rest of our dozy continent isn’t taking their infiltration seriously enough.) Attilio shared with us the best estimate of how many Sicilian businesses are still paying pizzo — an astonishing 60%-70%. His face was wracked with fury as he explained that only last year a local politician whose public behaviour could easily be decoded as Mafioso had been re-elected.

Sadly, the Mafia is not as unpopular as it ought to be on the island given the extent to which it has blighted economic development and human flourishing. Cosa Nostra moves with the times and the last big boss to be jailed, Giuseppe Guttadauro, was a qualified hospital surgeon.

As with the island, beautiful Teatro Massimo fell into disrepair for a long time. The restored auditorium has a perfect acoustic and everywhere you look the ornamentation is breathtaking. You can enjoy Italian opera in Palermo for a fraction of what it would cost at La Scala, Milan. I was gutted to miss Otello but had to come home for the sake of my Mum, and I heartily recommend you take that budget flight from Manchester or Stansted.

And the theatre has another space. It is a large, circular breakout room where the acoustics are different. This room echoes, by design. If you stand at the very centre and recite a line from Shakespeare (drama queen that I am, I’m afraid that’s what I did) your voice will bounce and reverberate endlessly off the walls.

This is Sicily, where the deafening noise of an interval crowd will disguise the whispered conversations of men who do not wish to be heard.

Deafening whispers

Although Addiopizzo offers legal and practical support to victims of extortion, an important focus is cultural resistance. Remember those simple folk who thought the pizzo was legitimate? That it was just “putting yourself in order”? Signs, artworks, memorials, provocations and interventions help to de-normalise the extortion racket. And just like Father Pino, Addiopizzo tackles social exclusion and educational poverty.

Above all, they tackle omerta, the Mafia code of silence and looking away as the money envelope is handed over.

In Sicily the artistic community has, to an extent, stepped up. Can the same really be said for Yorkshire’s artistic community? In Part II I will argue that in the North of England, underneath a cacaphony of moral engagement, we’ve perpetrated our own omerta. I will explore what lessons, if any, can be learned from the Sicilian experience, and I will consider some ways in which we, as Northern writers, artists and theatre-makers, can make amends for our decades of silence.

Expect Part II in a few weeks time.

Highlights: Jan 25-31, 2025

In the dreck of January you’ll find more theatre folk enjoying a budget jaunt to a sunny holiday island than treading the boards. January is a time of exhaustion and reflection. But there are a few things on next week that are worth a look:

LAST CHANCE: Leed’s Playhouse’s Christmas show The Lion, The Witch And The Wardobe ends on Jan 25, £15-£65, last few.

Amateur company BLT presents Lucy Kirkwood’s comedy NSFW (Not Safe For Work). It’s set in the offices of a contemporary publishing house where the staff of Doghouse, a lad’s mag, clash with those of Electra, an empowering women’s journal. It’s a riot of sexism, pornography, free will, consent, and post-University angst. Bingley Arts Centre, Jan 25, £12.

Whereas Is That A Whip In Your Hand? is perfectly safe for work. It’s actor Gavin Robertson’s cartoonish one-man parody of all our favourite fortune-hunter movies: “Indiana Jones meets National Treasure meets Romancing The Stone”. Family-friendly, inventive, and Neil Gaiman is nowhere in sight. Ropery Hall, Barton On Humber, Jan 30, £14 & £16

And finally…

Yes, I know. Veteran producer Ellen Kent’s opera and ballet company exists mostly beneath the posh papers’ notice. There’s too much traditional staging; not enough turning Puccini into a critique of colonialism or whatever. And she doesn’t use well-known opera stars. Wisely, she leaves all that to the state-funded sector.

But the thing is, she makes it work. She provides big spectacle on a shoestring budget, employing talent recruited from former communist countries whose Soviet-era academies churn out more highly trained dancers and opera-singers than their present-day economies can absorb. This year it’s the Ukrainian Opera & Ballet Theatre Kyiv.

Her Tosca, which I saw a few years ago, featured a golden eagle flapping its wings and threatening to take flight in the New Theatre’s auditorium. La Boheme, set amongst poverty-stricken students in 19th-century Paris, has the less intimidating Hugo, a border terrier, appearing as Muzetta’s dog.

Appearing for Ellen is Hugo’s sidehustle. His main job is as a valued therapy animal visiting care homes and old people’s hospital wards across Hull. Everybody go… ahhhhh! Hull New Theatre, Jan 31, with La Traviata is on Jan 30, both £17.50-£47 each.

Liz x

Nicely put. Interesting that the kids that challenged the mafia might (perhaps) be same kids who would be pc here. The upside and downside of the rebellious idealist energy of young people.

In the right circumstances they are a boon.

But in the globalised, democratic, prosperous, alienating, confusing consumer world here, there is an absence of an specific grounded enemy they can identify - they turn strange and hallucinatory in their search for a surface that will resist their chi

The final irony is that there are ultimately unable to process an actual evil on the rare occasions they encounter it.